Hernán Cuevas Valenzuela, Valentina Leal and Lucas Cifuentes

Fluctuations in ship movement and changing weather conditions produce variations in the landfall of ports and thus their labour needs. As a result, port activity has historically avoided establishing permanent salaried contract jobs because they would be inefficient or unsustainable for companies. Given the instability of the demand for dockworkers’ labour power, union struggles have aimed to regulate port work and protect access to available jobs. In other words, labour unions have tried to control the labour offer and distribution of the limited number of shifts among unionized workers based on organization through closed or union shops. La nombrada – literally the naming or the call – is the name this appointment practice takes in Chilean ports.

La nombrada intervenes in the hiring of temporary workers by offering of lists of unionized workers to companies that need to engage labour. This creates a labour regime that is very characteristic of port work. The system centres on two principles: First, control (and in the extreme, monopolization) of the labour supply by the union through lists of registered members, which they use to limit the employer’s hiring freedom, and second, solidarity among union affiliates in order to distribute the limited offer of job positions based on a fair division of shifts among workers.

Historically, this appointment system involved two phases: First, companies communicated their needs to the unions through hiring offices, specifying the number of workers and type of labour required per shift. In local slang, this was known as la pedida (the demand), which was the prerogative of port companies or ship owners and was carried out by a port official. The assignment of appointments occurred in union facilities under the jurisdiction of the maritime authority and during hours set for each union. Secondly, the unions, their leaders or a designated body responsible for the appointment system had a book with all of the names of affiliated workers and would call on – or name – the workers registered in the union lists who had permission to work. The appointments process followed a strict order and the union could not skip over a worker unless the maritime authority had suspended an employee.

This practice allowed the unions to: 1) influence the number of port enrolments used, 2) control the labour supply in ports, 3) influence port tariffs and salaries, and 4) control ownership and distribution of labour.

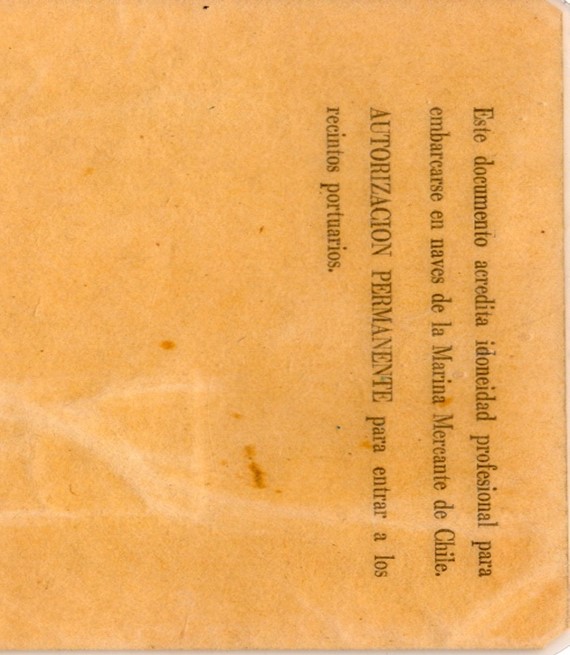

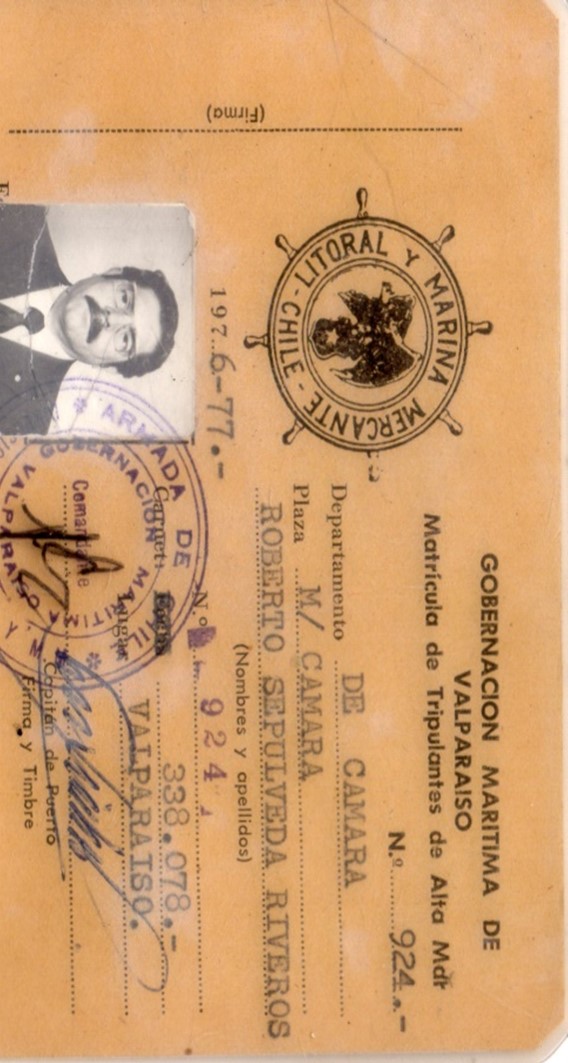

Established through a nominative registry, enrolments took the physical form of a non-transferrable identification card with the holder’s photograph and personal information. Workers thus became ‘owners’ of a position. Workers had to request an enrolment in the hiring office. In order to fill the number of vacancies, the hiring office had a ‘preference list’ that mainly consisted of relatives, close friends and substitute workers (the so-called pincheros). These barriers to entry of the labour market in the ports favoured higher salaries and generated a clique or ‘closed’ social world based on a dockworker culture of internal solidarity.

Working Permit of the Port of Valparaíso (Matrícula Portuaria de Valparaíso). Photograph by Valentina Leal.

The unions used port enrolment along with the convening of the appointment system as a mechanism for controlling the labour offer. One interviewee reported that in this way, ‘the workers were the owners of their labour’. This image underlines the importance of the figure of a worker who works for himself, as a free subject, and not as a salaried employee who works for the benefit of a company. This was an emancipatory imaginary common among dockworkers. It stressed autonomy and independent work but also petty bourgeois aesthetics that were consistent with stories describing dockworkers as a working class aristocracy.

The control of the labour supply gave the union enormous structural power – to influence and strengthen their demands with respect to threats in the labour market and to oversee the process of working in the port and in the economic system as a whole. One of our interviewees recalled that ‘the port unions were very strong, very strong. They could make the entire country grind to a halt’.

Furthermore, the practice of la nombrada consolidated the union’s power of association. As all appointments were union members, being a union member was attractive to workers. The arrangement made it possible for unions that monopolized the labour supply to capture a significant part of the high income generated by port activity. It also allowed distribution of financial resources beyond just the few assigned jobs, reaching the rest of the population in a type of trickle-down effect associated with high incomes, levels and styles of consumption and the dynamics of family formation. This accumulation of power enabled unions to ensure high incomes for dockworkers. Several informants remembered with ambivalent nostalgia the period of bonanza during which some dockworkers even had the economic capacity to maintain more than one family and a bohemian lifestyle.

In addition to the primary salary benefits resulting from collective bargaining with the government and the Chamber of Shipping, unions granted health benefits, training and education, and educational scholarships for workers’ children. They also promoted leisure activities and celebrations that promoted social solidarity and enhanced workers loyalty to the organization. La nombrada allowed unions to better deal with situations of eventual, contingent and temporary work, minimizing the impact of job and social precariousness usually associated with extreme labour flexibility. However, pincheros (temporary workers) remained in a situation of extreme vulnerability and precariousness.

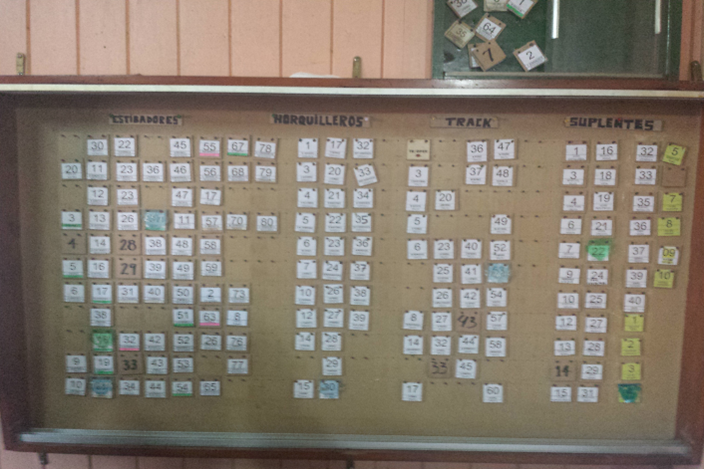

Pictures of the Sala de Nombrada Sindicato N°1 de Estibadores de Valparaíso. Auditorium where La Nombrada used to take place. Photographs by Hernán Cuevas, 2017.

The trade union structure we have described refers to the period prior to September 25, 1981, when the Pinochet regime passed Law 18032, transforming the regulation of work in Chilean ports and liberalizing the labour market. This law modified, among other things, the union structure and the role that the unions had played up until then. It consolidated the disappearance of the indirect control exercised by the unions over enrolment, and the direct control over labour supply and the distribution of shifts through la nombrada. The immediate effect was a dramatic reduction of wages offered for each shift and the drop of direct employment in ports. However, la nombrada did not disappear altogether. How to explain its survival well beyond the legal modifications introduced in 1981 by the Pinochet dictatorship?

Certainly, one factor that explains the survival of la nombrada as an appointments system is union resistance. From the perspective of labour, the system has the effect of securing a minimum level of employment and salaries for union members. However, la nombrada is not only an appointment system but also a social practice that strengthens the associative, structural and institutional power of unions. It allows for the organization of a dispersed workforce, bringing together the strength of many members to build trade union solidarity and obtain a better negotiating position that increases participation in terms of corporate income. This last aspect of la nombrada restricts the labour market and hence empowers the bargaining power of unionized workers. The structural power of dockworkers also rests on their collective capacity to produce logistical and economic disruptions. In Valparaíso, the effect of the mere threat of a stoppage during fruit export periods extends beyond the port area, affecting the entire logistical chain and production network of these perishable export products.

In the case of the Valparaíso, our evidence indicates that unions have lost power in terms of their associative strength, especially if we compare them with the unions of the 1970s. The loss of affiliates, the appearance of more unions, the reduction of their organizational capacity, the decline in the commitment and participation of members, the lower level of solidarity and internal cohesion, and the insufficient availability of material resources and access to expert knowledge are some of the factors that influence this loss of associative power. Although in all these factors the unions of Valparaíso have lost vitality, their continued existence seems largely to derive from the influence they still maintain on the placement of workers.

Today, many unions maintain control of the appointments system in ports across Chile. The situation of the largest union of temporary workers in the port of Valparaíso (Sindicato n° 1 de Estibadores de Valparaíso) is ambiguous in this respect. In Terminal 1, tendered by Terminal Pacífico Sur (TPS), the company allocates workers from lists of affiliates provided by the union. In this case, the union’s strategy has been to accept the company’s appointment system while maintaining close contact with management to favour the hiring of a majority of union members. In contrast, in Terminal 2, tendered and operated by TCVAL, the union controls staff appointments, which it coordinates with the company’s human resources department. This form of operating has assured a number of stable work sources and shifts. The position of Valparaíso’s main union, which involves negotiating different mechanisms with different port companies, is representative of its leaders’ pragmatism. This pragmatism is also visible in the way the leaders distance themselves from any class-based discourse. In an interview, the President of this union defined its objective as the maximization of its participation in both the product of port business and the total number of shifts. Hence, it is not surprising that during the dockworkers national strikes in 2013 and 2014, the dockworkers of Valparaíso continued to provide logistical services, even increasing their demand during the months of national stoppages.

Private companies operating ports have tolerated la nombrada because it favours a flexible hiring modality that is useful to meet changing labour requirements. Their business strategy is somewhat ambivalent. On the one hand, companies try to diminish the power of the unions, favouring their fragmentation. The Chilean labour legislation introduced during the military dictatorship served this purpose. On the other hand, companies ‘need’ unions to maintain and control an available, trained and flexible workforce. Furthermore, unions reduce the companies’ transaction costs because the appointments system of la nombrada offers them the option of hiring of an ever-available workforce of numerous casual workers, who are flexible, organized, disciplined and experienced without the costs associated with a highly segmented labour market with information asymmetries.

In Valparaíso, unions have exploited a close relationship of dialogue with private concessionaires. It is difficult to determine the extent to which the transactions between unions and companies represent a clientele-type co-optation relationship and subordination of the union, or if in contrast, the union manages to negotiate at the same level as the company. As suggested above, the union does not work in terms of a class logic, but acts as a business participant providing the functional equivalent of a staff contracting company.

Throughout history, la nombrada has received criticisms related to the promotion of clientelist relationships between leaders and partners/workers; for being an inequitable, opaque and flawed distribution mechanism of shifts; and as a practice that has sown mistrust among unionized casual workers and their leaders. Conservative newspapers and think tanks linked to the business sector have constructed la nombrada as a moral panic around perceived risks of ports being captured by dockworkers unions and their mafiosi leaders in detriment to the national interest. However, some of our interviewees criticize the staff placement undertaken by companies. They report irregularities of a ‘black list’ type to exclude workers. They also report abuses such as the non-payment of overtime hours outside of completed shifts, or the assignment of multitasking. In addition, we have collected accounts of preferential treatment obtained by some workers.

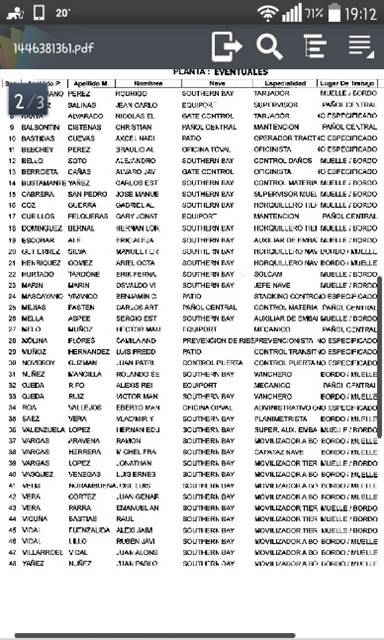

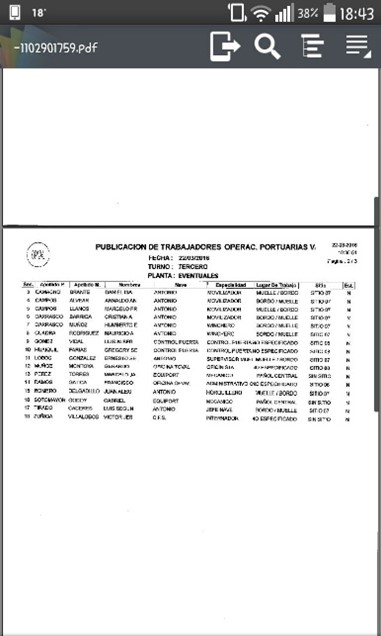

In recent years, an attempt has been made to formalise and regulate the appointments system to eliminate its shortfalls. In this way, the heterogeneous current scenario of forms of hiring and recruitment of casual workers in Chilean ports has begun to give way to a certain institutional convergence toward forms of appointment deemed more democratic and transparent. These changes involve limiting the direct participation of union leaders in appointments to avoid ‘finger-pointing’, producing guidelines to formalise the call process, the list of workers and its rotation (la redondilla), and enhancing the union assembly control of la nombrada. Along with these changes, there are other minor modifications between old and current appointments system practices. Instead of someone calling out names in a room full of people – the appointments room – digitized lists are circulated. The Internet is also used for dissemination, and workers are often contacted by telephone or even Whatsapp.

Picture of an old board system compared to a digital list of dockworkers. Photographs by Lucas Cifuentes and Valentina Leal.

The continuity of the appointments system of la nombrada and the changes it has undergone derive from its functionality for both companies and workers. In other words, la nombrada has facilitated the coupling between business and union interests. Chilean port labour regimes result from a variety of contingent labour-capital arrangements, allowing for different accommodating solutions and appointment systems.

In the hands of unions, the appointments system is a social practice that functions as a mechanism of power. It allows union leaders to: (1) organize a dispersed workforce, (2) exercise leadership among their members, (3) build union solidarity, cohesion among members and to accumulate the strength of many members and, potentially, (4) monopolize the labour supply.

At the same time, the appointments system provides benefits to companies by allowing them to reduce the high transaction costs that would result from the need to produce staff placement according to a logic of ‘just-in-time’ in a flexible and disarticulated labour market, such as that of the port sector in Valparaíso.

The appointments system may be more likely to remain if it manages to match the interests of workers to maintain jobs (or shifts) and levels of income, and the interests of companies to access a flexible workforce at low cost. Placing staff based on the daily labour requirements of port companies with a fundamental role played by the unions seems to lessen the negative impacts of labour precarization, making dockworkers’ flexible work scheme less vulnerable to the vicissitudes of the port logistical sector, more predictable and safer.