Carolin Philipp

Pier II at Piraeus is a site where various transnational transportation networks coalesce. Leased to China’s Cosco, the global hub receives, reloads, transfers and consigns goods stored in containers. Pier II is mainly used for the trans-shipment of containers that – immediately and without taxation – leave the harbour after being reloaded on a subsequent ship. Less than 20 percent of the containers that leave the Pier are loaded on rail or heavy-goods vehicles to continue their journey further into Europe.

Cosco operates within a flexible network that exists in geographically remote but highly connected zones of exception, largely detached from the surrounding societal and economical infrastructure.

The former dockworkers of the Ikónio neighbourhood overlooking the pier, the sailors at Piraeus as well as the industrial zone of Pérama west of Pier II are seemingly untouched by Cosco’s logistical networks.

According to the narratives of the area’s residents – small scale tradesmen and local workers employed in ship-repair and the metal industry – the traditional labour and industrial networks have long been globalised but at the same time have maintained strong local links with small scale businesses. The traditional economic and labour networks surrounding Cosco’s Pier II are a locally tightly knitted fabric of deeply interdependent entities, hierarchically structured from large industrial factories with large workforces, small and middle scale enterprises to semi-legally self-employed individuals. If one actor ceases to exist, the whole system is affected. Their mutual local dependencies seem disadvantageous in comparison with the geographic flexibility of global players.

The deterioration of metal industry located at the Western end of Asprópirgos illustrates this phenomenon. It hosted two major Greek steel factories: Ellinikí Chalivorugía and Chalivourgikí. Once a significant industry, the steel sector has been seriously hit by economic decline and austerity, resulting in the closure of one factory in early 2014. The industry produces a certain amount of steel from used metal instead of more expensive ‘freshly mined’ materials. Southeast of the plants, an industrial zone accommodating the ship repair and building industries sheds huge amounts of scrap metal to be recycled. The mandres, the metal collecting yards, gather and assort these materials. When the ship repair business declined in the course of recession, it provided less and less cheap material for the mandres and the steal factories. Simultaneously the demands for steel in the domestic building sector dropped while in the export sector in neighbouring Turkey emerged as a competitor. These tendencies combined with spreading unemployment intensify an occupational phenomenon: the collecting of metal scrap in the streets. Although they represent the end of the chain in the metal industry, the individuals engaging in this line of employment share some common characteristics with the global corporate actors of Pier II.

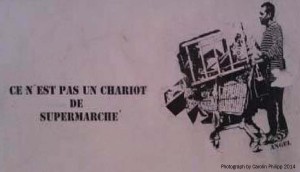

The scrap collectors work in the neighbourhoods surrounding the Cosco pier. They tour the area with small vehicles or supermarket carriers. Container trucks thunder by as they gather valuable material for recycling. They pick up all kinds of used metal: old cables and wires, rusty bedsteads and colourful oil canisters. Unlike the operators of global trade residing in the isolated Cosco offices down at the harbour, the scrap collectors are visible and present on the streets but seemingly unconnected to global networks.

However the narratives of the collectors tell stories of flexibility, border crossings and global connections: the refugee from Asia Minor with experience sailing the seas in a fishing trawler, the Pakistani who has journeyed to the European periphery aiming to reach his brother in Germany, the Albanian Roma who has constantly migrated before settling in Athens. The collectors have various backgrounds of African, Asian, Greek or Roma descent. They came to Greece in different periods, by different routes, by different means. Many of the local Greek collectors have a history of a variety of professional occupations, of travelling and migration.

A Greek collector from Keratsíni explains:

I am educated, I was a mechanic. All my life I was sailing the world. India, China, Australia, Africa, South America. I have seen everything. I am 74 and have a small pension, but it is not enough.

The image of dirtiness inherent to the places where the scrappers find the valuables – the trash bins – subsequently becomes associated with their work or even the person of the collectors themselves. This image is not always adopted by the scrappers though. Many are concerned about state control and reluctant to speak to strangers. They discuss their occupation as a matter of fact or even as a healthy exercise.

I don’t consider it as work. I am 83 years old. (Yes, I know. Many people say I don’t look like it.) I do it for my legs, when I sit too much, they are getting old.

Mostly self-employed, the collectors enjoy a certain kind of independence. Like other freelancers, they individually decide about their working hours. Yet they also have to adapt to the functioning and the schedules of the connected industries.

You are asking why there is nobody on the street now? I don’t have fixed hours. I don’t have a boss. I work whenever I want. Morning, afternoon or evening. In the afternoon it is better because in the morning they collect the rubbish from the city.

Their tales of global connections, leisure activity and independence are tinged by marginality, and exist on and transgress the borders of legality. While the authorities stretch competition rules in favour of the influential Cosco, they increase pressure on small businesses like the scrap industry via strict control. According to the research of documentary film-maker Christos Karapelis, the old generation of scrappers wished for state control to support the individual collectors against the arbitrary price politics of the scrap yards. Now however they have become subjects of illegal practices themselves. A new law established at the beginning of 2014 demands numerous permits in order to pursue metal collecting. A lot of scrappers lack legal papers of various kinds. Consequently the amount of metal brought to the mandres has dropped by half since January. One madras owner remarked:

Now with the new law we need to check the VAT number, address and driving license of the scrappers. To check if they are working legally and if the material is stolen or not. We play the role of the police.

When a collector without the legal requirements sells metal more than three times a year he or she is considered to be running an illegal business or bypassing the tax system. Considering the profits of large corporations bypassing the tax office as a result of corruption or ‘promotion of economy’, the persecution of scrappers seems rather disproportionate. Refugees who are improvising to substitute the de-facto non-existent asylum system or Greek pensioners affected by the government’s austerity cuts are forced into illegality.

As the economic situation of the majority population is constantly declining, the composition of scrappers is shifting. Certain groups are abandoning the trade while others are entering the business. Traditionally the scrap trade was dominated by Greek Roma. In two mandres, the workers stated:

There used to be more Greeks, especially Roma. But they couldn’t keep their cars because of the tighter controls and the taxes. They didn’t have the license to sell the scrap (only for selling carpets). So the Roma are gone from the business.

Migrant scrappers emerged on the streets in the course of Greece becoming the main entrance for migrants and refugees to Europe. When the state fortified its borders as a requirement of the Dublin treaties, the country turned into their inescapable station of detention. Many of the newcomers became scrap seekers. With the increasing economic deterioration, the pressure mounts on them to become again globalised subjects ‘on the move’. While most are excluded legally from global strands of migration and transportation, they find loopholes to continue migrating, looking for a better life elsewhere.

I worked in construction before I started collecting metal. In construction there is no work anymore. I’m 17 years in Greece now. Nearly all Pakistanis have left because of crisis. My brother is in Germany. Now for 5 years I collect metal, that’s the job left.

But metal collecting also becomes increasingly laborious as less metal is discarded by private households while the number of scrappers is increasing. The economic decline of the area drives long time residents to become scrap seekers.

The foreigners collect during the day, the Pakistani, the Bangladeshi, the Bulgarian. The Greeks are ashamed. They collect rather in the evening.

The migrant scrappers are mainly seen as population in transit, although some of them have become ‘new locals’ mainly focussing on working in their own neighbourhood and considering themselves as residents. When asking an Albanian Roma where – after he had been living and working with his six-person family in Kateríni, Lárisa, Lamía, Domokós and other places – if he intended to move on because of the difficult economical situation, he replied:

Why? Should I go back to Albania? I have no house there. My family is here, so I am here.

Many of the collected statements reflect phenomena existent also in the majority society. While many Greeks consider long-term residents with non-Greek origin as foreigners, the subjects themselves, like the above testimony, regard themselves as locals. Mainstream discourses about the ‘increasing migrant population as a problem’ also exist among the scrappers.

There is a lot of antagonism between Greek and foreigners that do the same job. The foreign nationals take our jobs.

The construction of Greek identity has shifted with the newcomers in business. Formerly disassociated groups now include themselves in a broader definition of ‘being Greek’. A Roma scrapper – who by mainstream Greek discourse is not included in the definition of being a ‘real’ Greek – refers to Pakistani and Bangladesh collectors as ‘foreigners’ but sees herself as Greek:

There should be only Greeks like us looking for metal … The Pakistanis now are coming and taking our jobs.

Labour relations in contemporary Greece are becoming increasingly precarious but the scrappers are a group the end of the economic chain that has always been the embodiment of precariousness. Their narratives speak of flexibility, mobility and assimilation to extreme changes as normality.

Before this I sold water, carried luggage, cleaned shoes. I didn’t study very much because I could not pay. But when I worked 15 years in the refinery (Ellikina Dilistiria), 12 hours a day, I became assistant to an engineer. But then there were some problems and I had to change … I worked on fishing trawlers, sailed the Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean, South Africa.

Being exposed to economic crisis, competition for scarce resources and governmental repression once again, the scrappers will have to find ways to adapt or change their trade routes, their occupation or their location. Having histories and experiences of flexibility and precarity, they might at least have an advantage here as their lives always been characterised by constant change and movement.