Jamie Allen

Can anything be made without extraction? Are there modes of productivity that do not transport materials out of one place and into another, and in part just by doing so, create derivative value? Where does the impossibility of ex nihilo creation leave us, as empirically minded, self-supposedly creative humans who wish to add something of our own to a common world; who offer up perspectives and render contexts in ways that we hope will preserve and service the integrity of communities, materialities and justice? Are the patriarchal, colonial, racist and exploitative roots of modern capitalism and empirical research so intertwined as to render the motives of everything we see, and make from that seeing, complicit with these common d(en)ominators?

For more than a century, the South American nation of Chile has seen the materials and character of its territories rendered into commodities, largely servicing the interest of monetary profit both foreign and domestic. In this, Chile is rather like my own birthplace of Canada, a country that has quarried minerals, hewn wood and drawn water to sustain the wealth of that nation. Chile’s shifting fortunes, however, have repeatedly intersected with discernable technical rearrangements, three great booms and busts of hype and actual productivity in agriculture, communications and energy. The Canadian Shield was allowed to become a more stabilized bedrock for the extractive industries of the North, which would not profit as quickly or inordinately from the agile synchronicity of globalized logistics of shipping, nor suffer as dearly from the fragility of global commodity markets that these economic cycles bring about.

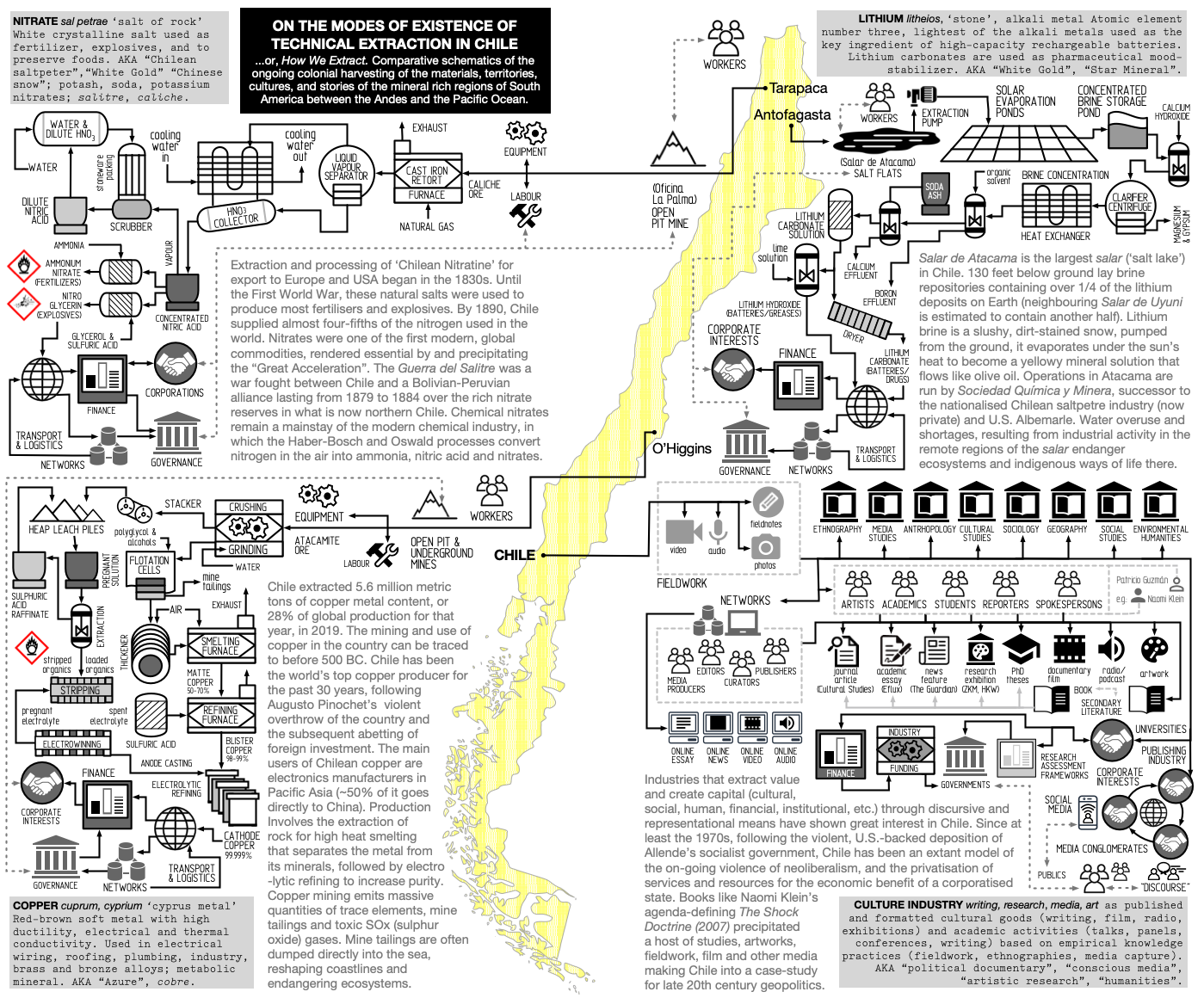

The fortunes and failures of Chilean resource extractions are a subtext of the stories we now tell ourselves about the Anthropocene, of the ‘Great Acceleration’ and the elaborations of modern industry that such curves diagnose and extrapolate. The continual surge of hastened productivity, starting in the mid-20th century and continuing into our current moment, began as a continuation of a European addiction to (agricultural) productivity that was initially fuelled by injections of fertilizer provided by saltpeter extraction from Chile. This addiction became the backdrop of post-war synthetic chemistry innovations that could pull nitrogen from the air, instead of from the Atacama desert. Solutions like the Haber-Bosch process would thereafter provide Germany and the world with their nitrate fix, driving Chile’s saltpeter industry into the ground, almost overnight. Another Chilean commodity, copper, is a primary raw material for the electrical, electronic and information economies that flourished through the last century, re-invigorating Chillean extraction in the post-nitrate era (many of the conglomerates selling saltpeter would convert their operations to copper). And just as the cupric arc of technological lock-in plateaued, Chile’s commodity futures would again prosper through the harvesting of lithium deposits within the country’s borders. As high-capacity lithium batteries emerge as the means by which continuous flows of electricity will be provided from less-continuous sources of energy like wind and solar, Chile finds itself with yet another elemental resource curse, another portion of its landmass which global markets are driven to extract, another ambiguous burden of riches that must be negotiated against the sanctity and non-monetary needs of communities and environments.

‘Research’ is a word we use for work that prefigures or is juxtaposed to ‘production’. For some, research is an activity that cross-cuts the cognitive labours of writing (in, say, the humanities), media making (of, say, documentary film) and other creative work (of, say, media making, art or design). Since the millennial turn, the disposition of research known as ‘fieldwork’ has become pronounced in the study and rendering of infrastructures, global politics and ecologies in peril. Numerous field trips, platforms and group expeditions have taken place that attempt to grasp the effects and planetary magnitude of global capitalism, as registered in particular instances and on particular sites, along the trajectory of a trans-Siberian train, in the case of the 2005 collective experiment, ‘Capturing the Moving Mind: Management and Movement in the Age of Permanently Temporary War’, or ‘Mississippi: An Anthropocene River’, also a collective research project and river journey on and along the Mississippi River in 2019. These empirical investigations in motion emerge when competing demands on time and a desire for interdisciplinary horizontality creates the need to conflate research and production, organize events and research opportunities that combine private method and public disclosure. In practice, they feel like a performance of both back-stages and frontstages, a breakdown of the modernist scenography that separates ‘research’ from ‘production’, as well as being a transformative ‘training’ of multidisciplinary subjectivities that are sensitive and situated.

These experiences of terrains and with people can provide comparative insight and topological connections, in measure with the systemic violence and exhaustion under study. They are also problematic ‘rites of passage’, as Shannon Mattern puts it in her study of field guides, and effective means of pushing knowledge practices and institutions from the security of abstract hypothesis and conjecture. The research collective I was a part of that visited the Valparaíso port systems, copper mines and communities of Chile for the Logistical Worlds project in March 2017 was all of this: as group of six or seven people, we visited a Codelco mining smelter; had lunch with local union reps at Port Valparaíso; conferred with foreign and domestic researchers, artists and activist; held discussions with astronomical data cleaners; ate, drank, joked and argued with new friends and fellow travellers, and variously collected notes and media that attempted to draw out how the long, narrow strip of land between the Andes and the Pacific Ocean that is Chile was continuing its long history of infrastructural-becoming. We were also given numerous powerpoint presentations, shown many systems schematics, process diagrams and illustrative operations plans, and plans for the future, most of which relied on or projected value created by extractive means.

Our varied group of researchers, activists, students, artists and media makers had individual and collective intentions and perspectives, sensitivities and emotional responses, that also, of course, morphed during our time together. It is a time for which I am immensely grateful, as for the continued connections I maintain with the situations and people I connected with in Chile. And as I diagram these material and knowledge processes, I am compelled toward changing how I understand and engage with ‘field’ and ‘work’, as well as the ways I myself render, use, profit from and critically reappraise these engagements. If the machinations of the mobile desire-machine of fieldwork can (as a mode of critical studies of environment, media and geopolitics) be brought to an abrupt if necessary halt by 2020’s COVID-19 pandemic, this has also provided an opportunity to see this kind of work anew, for what it is, what it is not and what it could be.